Treasury Bills Are the Best Place to Park Your Cash. Just Ask Warren Buffett.

Their 5%-plus yield looks attractive—especially with the Federal Reserve unlikely to cut interest rates soon.

Updated May 24, 2024, 9:19 am EDT / Original May 24, 2024, 3:30 am EDT

Investors large and small are gravitating to Treasury bills, thanks to yields of 5.4%, tax benefits, and sleep-at-night security—and there’s no reason for them to stop.

For a while now, Treasuries with maturities of a year or less, known as T-bills, have offered more yield than other U.S. debt offerings. That’s due to the so-called inverted yield curve, with short rates higher than long ones. The 10-year Treasury, for instance, yields 4.45%, while the three-month yields 5.39%. Bills have also offered positive returns—about 2% this year, based on popular exchange-traded funds—while long-term Treasuries are in the red.

For a brief moment earlier this year, investors avoided T-bills because of the expectation that the Federal Reserve would sharply cut short rates in 2024 and 2025, resulting in lower yields. But with short rates poised to stay higher for longer—Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon said this past week he sees no rate cuts this year —T-bill rates could stay close to 5% through the end of the year and above 4% in 2025, more than enough to offer a nice return after inflation and slightly positive real returns after taxes.

You’re able to earn income for the first time in many years at this point in the yield curve,” says Steve Laipply, global co-head of bond ETFs at BlackRock, referring to the range of bond maturities.

Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett is a leading proponent of short-term Treasuries. Berkshire is one of the largest T-bill investors in the world, holding $153 billion at the end of the first quarter, the bulk of its $182 billion in cash and equivalents. At Berkshire’s annual meeting, Buffett called T-bills “the safest investment there is,” saying he takes no chances with Berkshire’s cash. Buffett has long favored T-bills with Berkshire’s cash, even when they yielded close to zero from 2020 through 2022.

Individual investors have been following Buffett’s lead. Retail demand has been strong at the Treasury’s regular auctions of T-bills, of which there are $6 trillion outstanding. Noncompetitive bids at those auctions, a good proxy for individual demand, have averaged $15 billion a month over the past year, including $17 billion in April. That compares with under $2 billion a month in early 2022.

T-bills aren’t the only place to earn a nice yield on cash. Investors also have access to certificates of deposit, money-market funds, and high-yield savings accounts. But bills are superior in many respects to those alternatives. For one, T-bills yield more, with online savings accounts offering interest rates of 4.4% and Marcus, a leading online bank, offering a six-month CD at 5.1%.

Bills have a tax advantage, too. Their interest is exempt from state and local taxes—a nice plus in high-tax states like New York and California, where marginal income-tax rates can top 10%. Interest on bank accounts and most money funds is subject to state and local taxes. Even investors holding government money funds can be hit with these taxes because they often hold repurchase agreements—short-term loans backed by government securities—and not Treasuries.

“I love Treasury bills,” says David Feinman, a private investor and former high-yield bond trader. “They’re simple and high-yielding. For most people, T-bills are a superior investment to bank CDs.”

Retail investors can buy four-week, eight-week, 13-week, 17-week, and 26-week Treasury bills at the weekly auctions, either directly through the Treasury.gov website or at banks and brokerages, often without a fee. The 52-week bill is auctioned every month. Interest is paid out when the bill matures.

At Fidelity, there is no charge for retail investors to place noncompetitive bids online, and the firm offers an “auto roll” feature that allows investors to automatically reinvest the proceeds of maturing T-bills in new securities. There is a similar feature on Treasury.gov. With a noncompetitive bid, investors agree to accept the average yield set by institutional holders. There is a limit of $10 million of noncompetitive bids per auction—enough to cover nearly all investors.

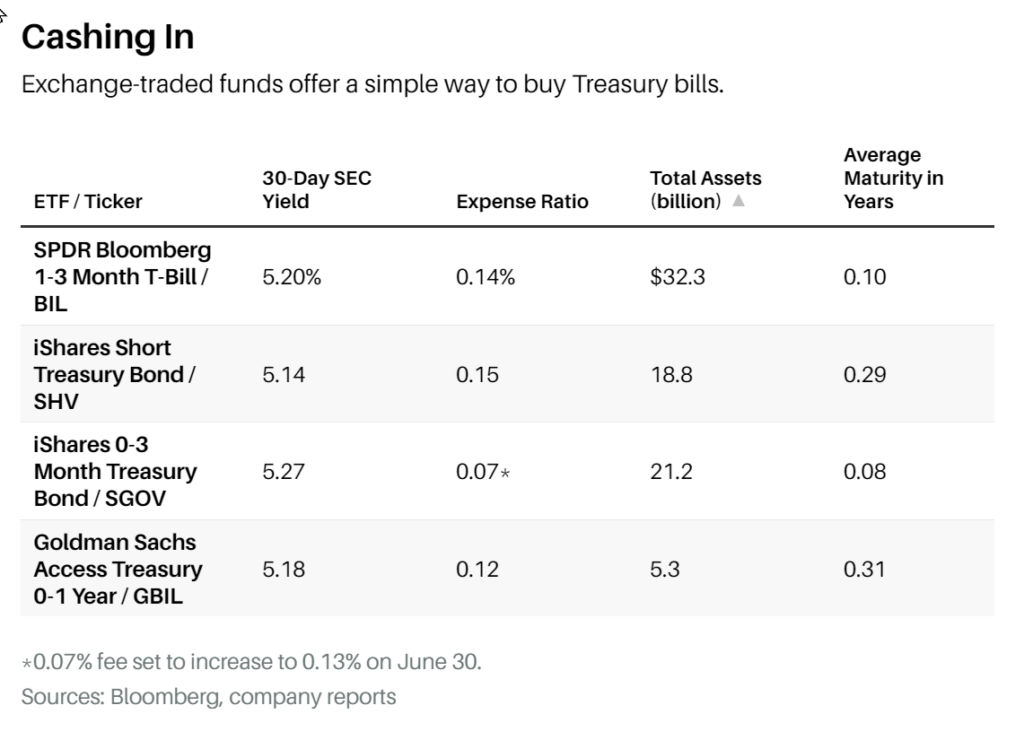

ETFs focused on Treasury bills are also a popular option. They simplify ownership, offer easy liquidity, and pay monthly income. The two largest ETFs are the $32.6 billion SPDR Bloomberg 1-3 Month T-Bill (ticker: BIL) and the $21 billion iShares 0-3 Month Treasury Bond (SGOV). Both yield about 5.25% and have little rate risk, given average maturities on their portfolios of about a month. Buffett favors three-month and six-month T-bills.

Bid/ask spreads are tight—usually just a penny, or equivalent to one basis point in yield, or a hundredth of a percentage point. Fees are low, at about a tenth of a percentage point annually. There is very little price volatility due to the short maturities of T-bills.

In addition to the SPDR Bloomberg 1-3 Month and iShares 0-3 Month ETFs, there are the $18.8 billion iShares Short Treasury Bond (SHV) and the $5.3 billion Goldman Sachs Access Treasury 0-1 Year (GBIL). Many financial advisors use these ETFs as an alternative to money-market funds for their tax benefits.